The Future of Digital Humanities

Digital Humanities is still a new concept to much of the academic community. Perhaps this is unsurprising; academia is a world of entrenched ideas where seniority is respected and few young workers are able to replace aging personnel. It should be no surprise that its leadership isn’t rushing to embrace every new advancement on the day it comes out. There are also very real concerns about the longevity and security of digital humanities projects which have left a number of my colleagues rightfully skeptical of the digital. In particular, corporate practices surrounding subscription models and AI allow Microsoft and similar companies to effectively hold academic work hostage or even steal it wholesale.

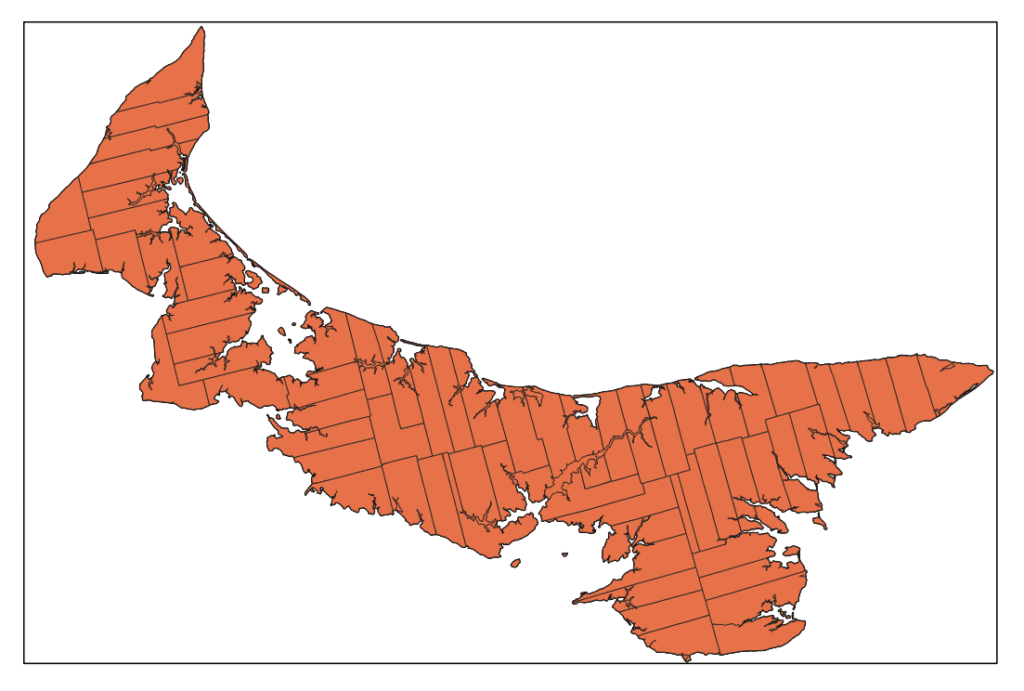

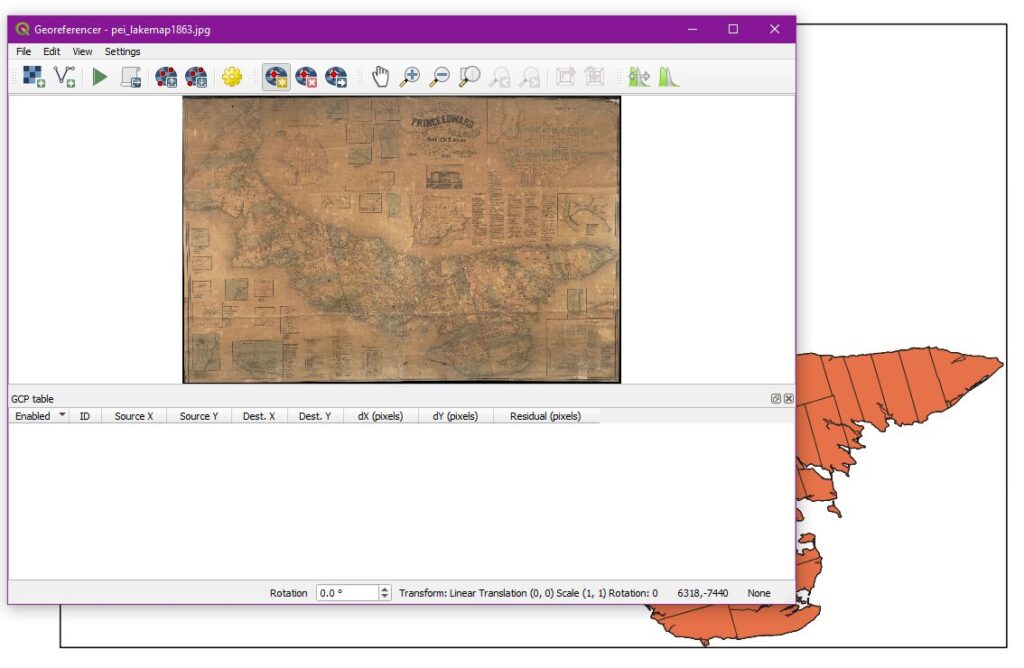

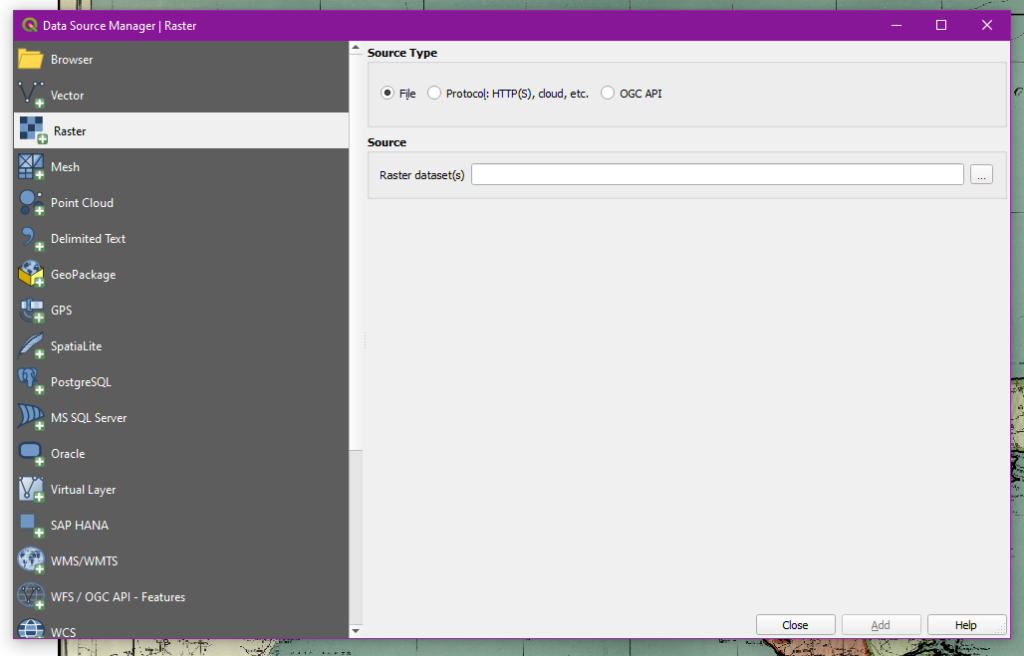

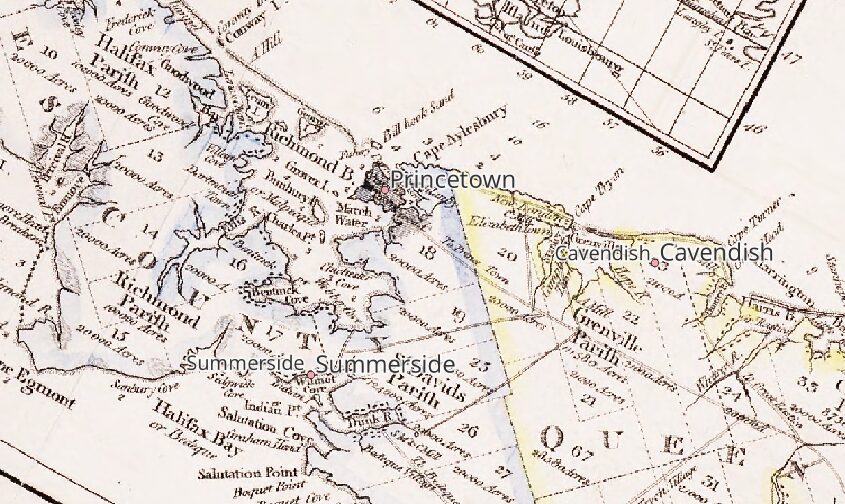

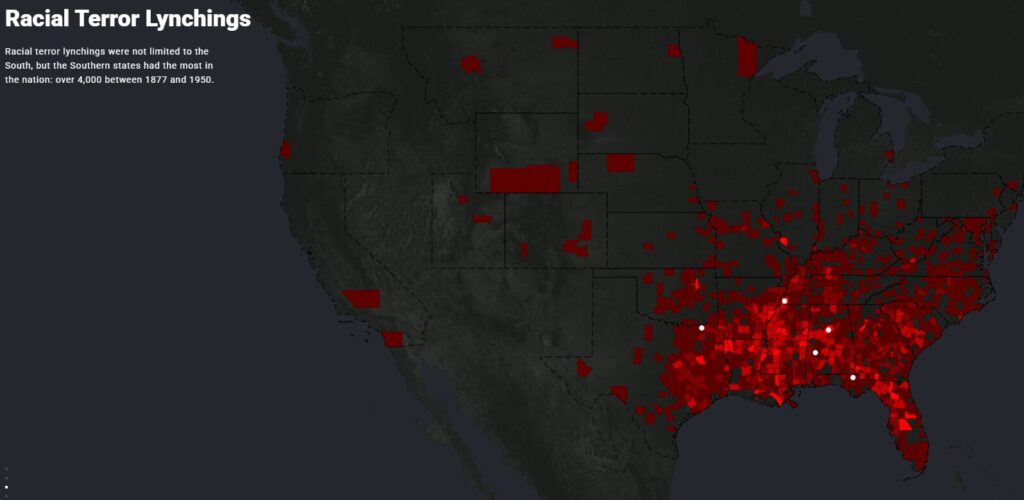

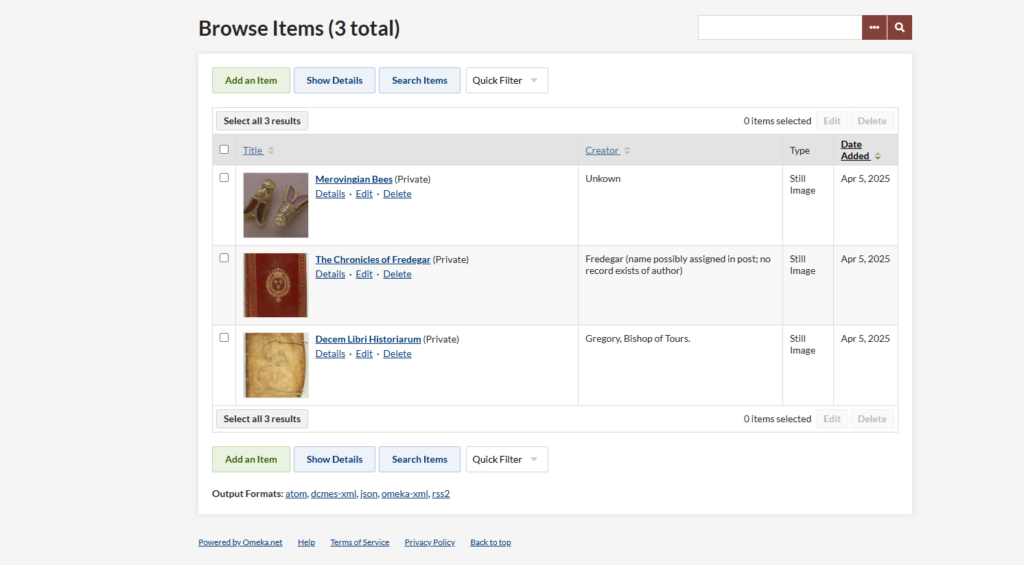

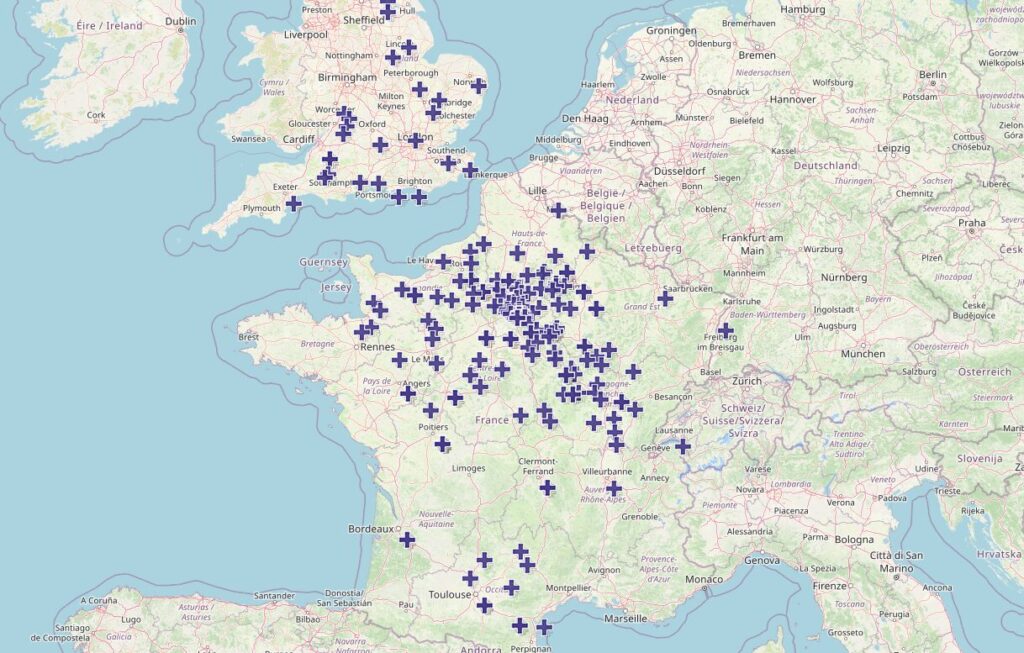

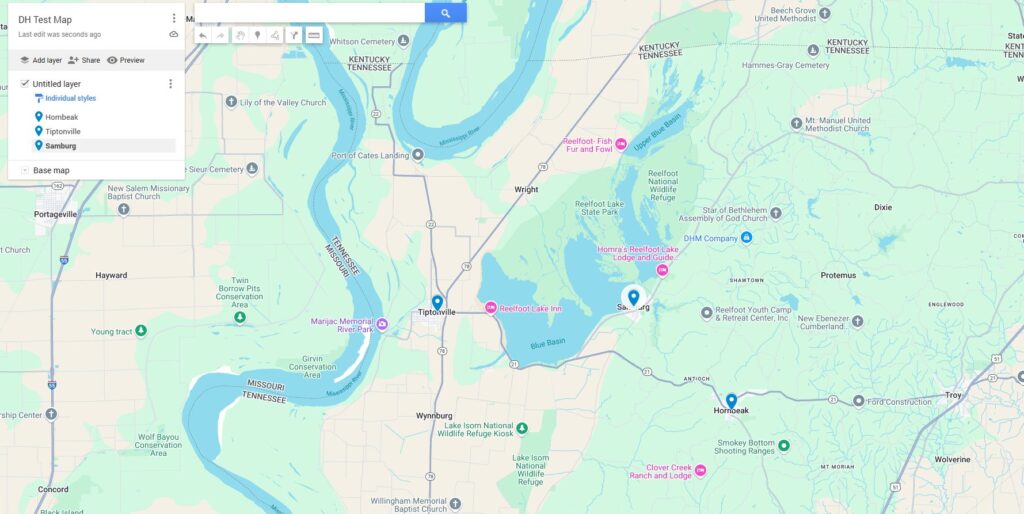

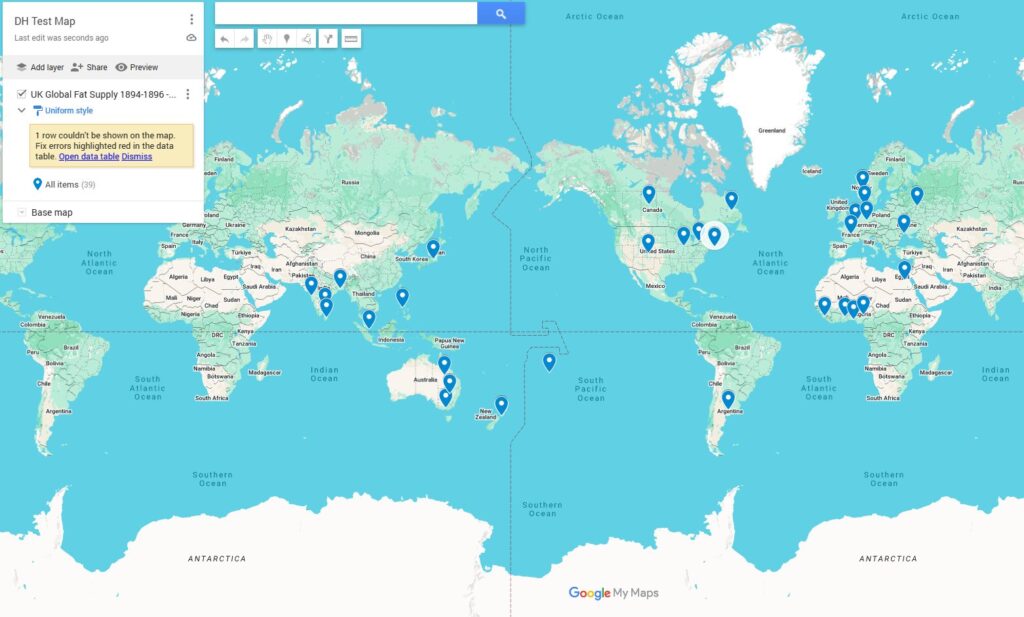

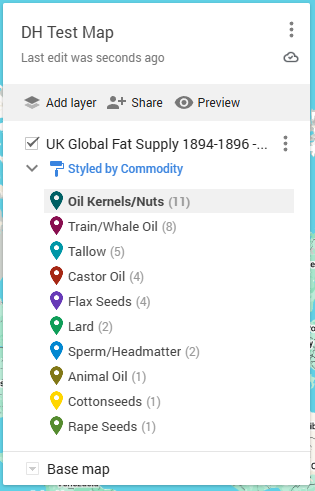

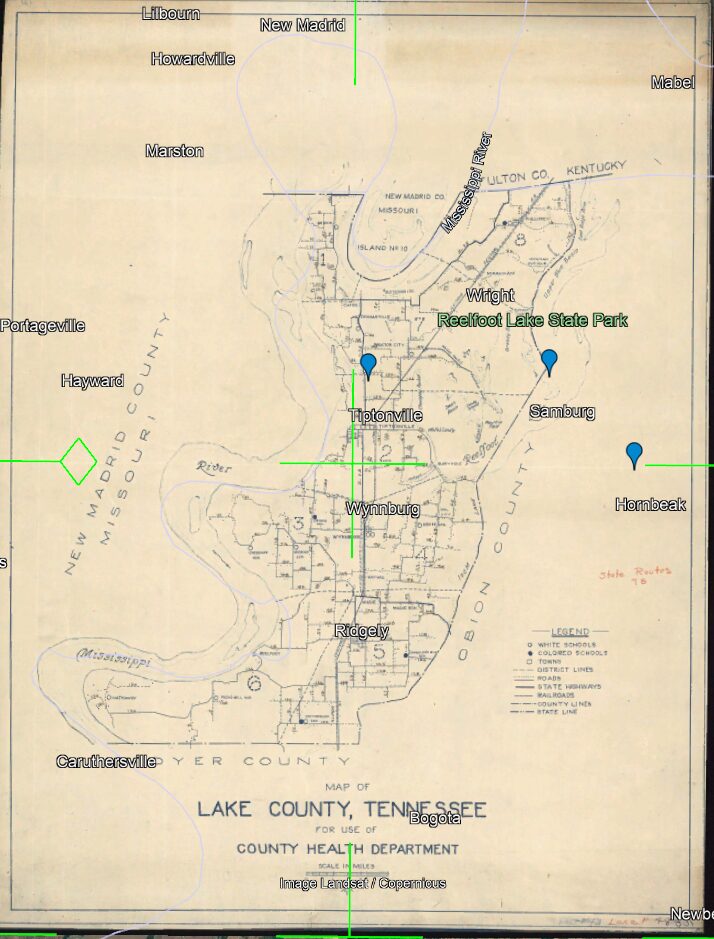

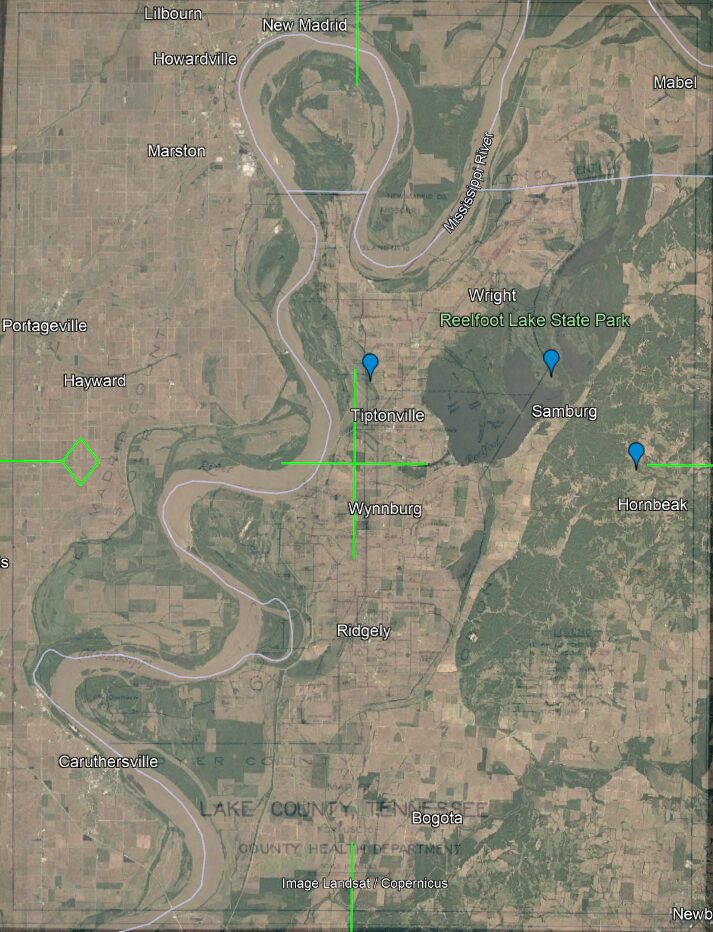

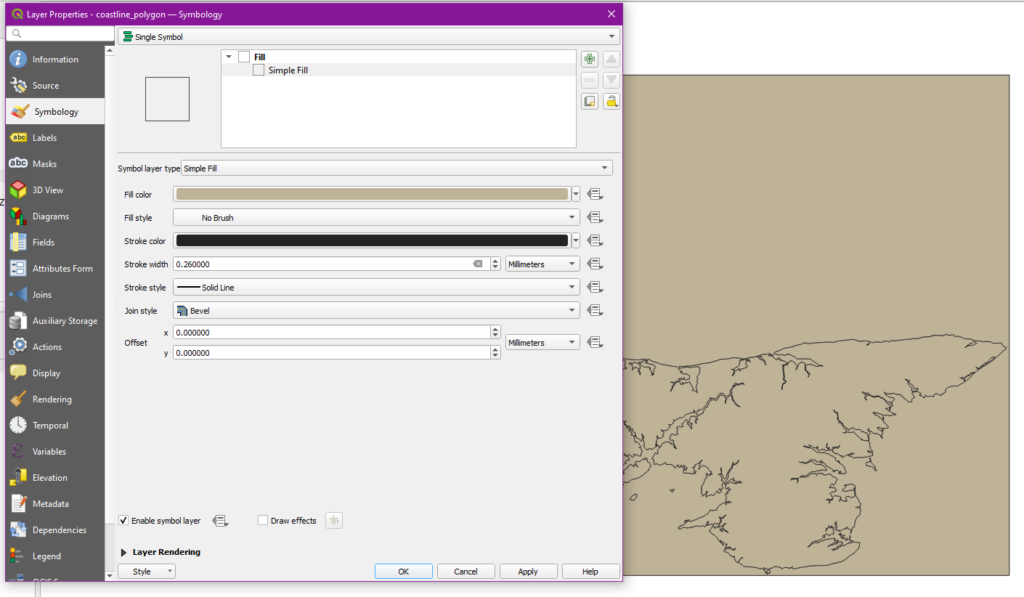

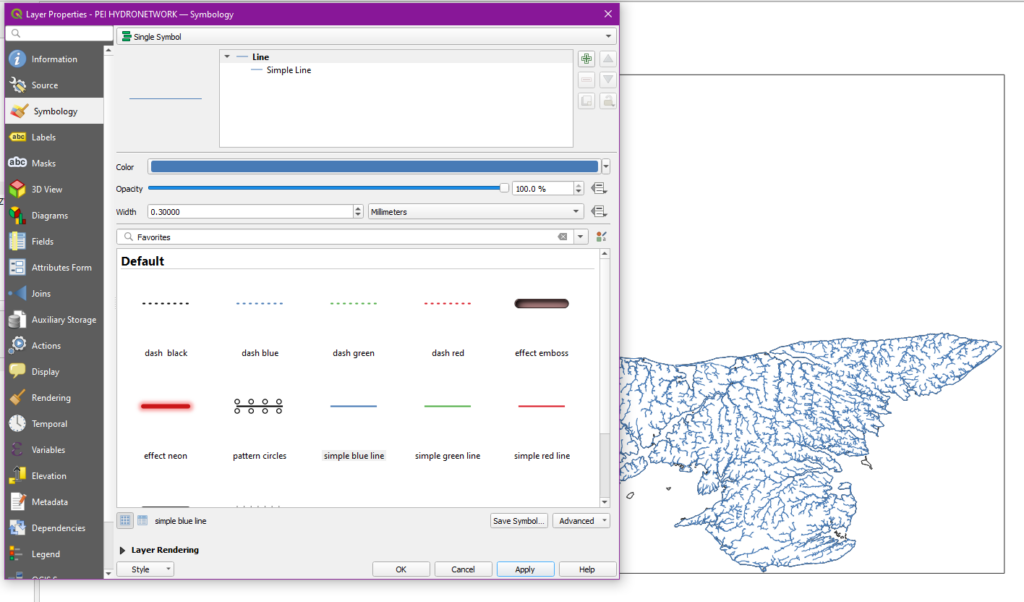

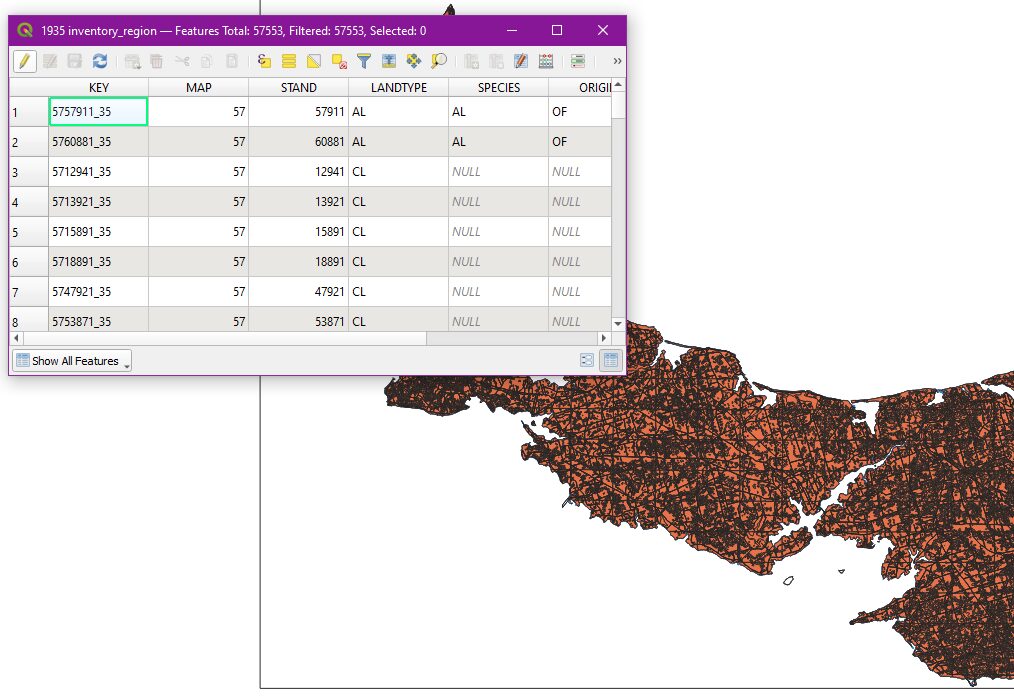

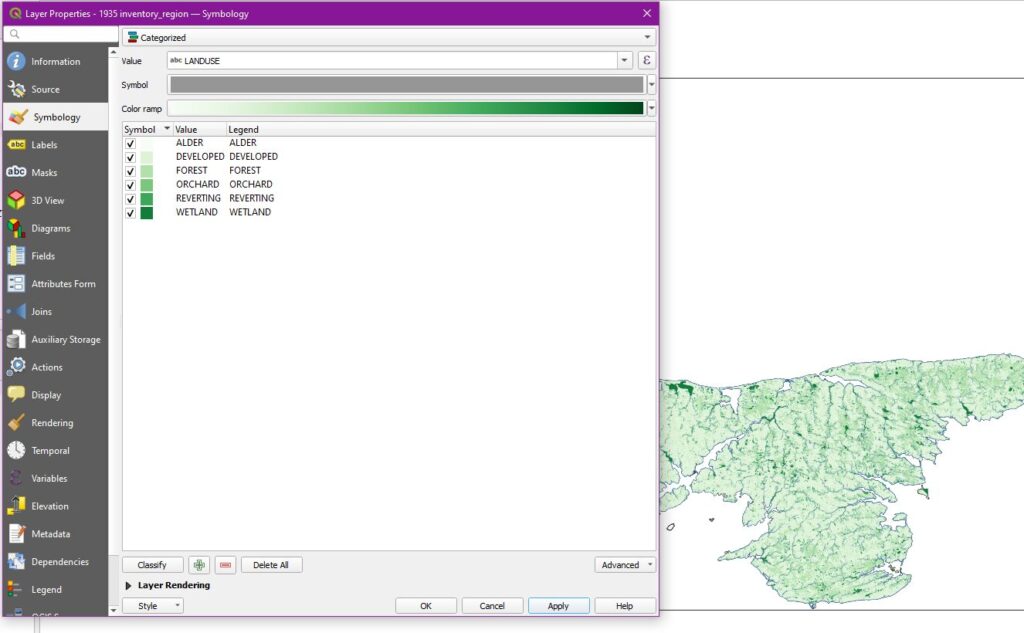

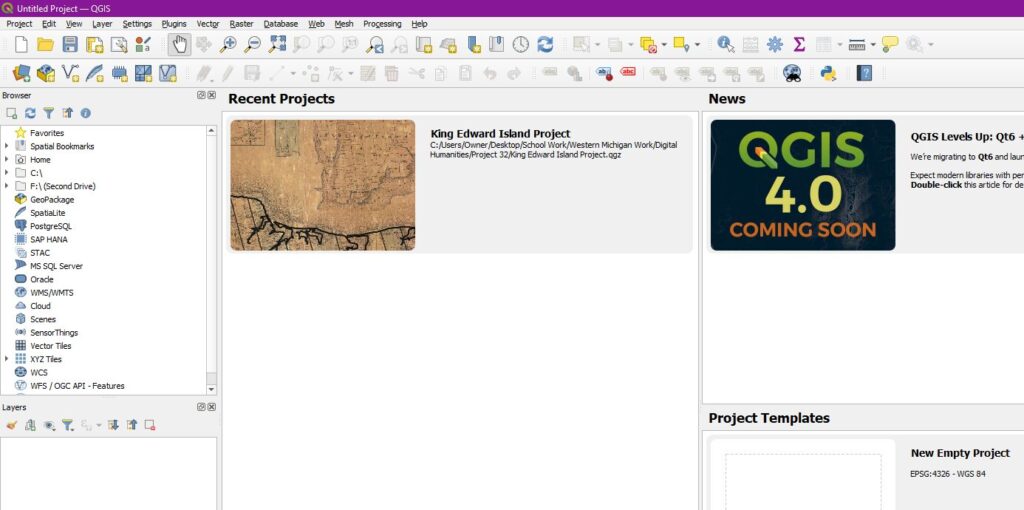

While cheaper and safer alternatives exist, they aren’t exactly making themselves user-friendly. Take QGIS, for example. I’ve noted in the past in these posts how effective and excellent this program is, but look at the user interface.

The number of buttons on this screen is frankly terrifying, even to someone who grew up with computers like me. My grandmother wouldn’t know where to start with this and plenty of academics fall in her range of digital technical skills. “Just learn it” works for one or two programs; it’s what I’m doing with QGIS. But that mindset falls apart when a dozen programs become interconnected, as is often the case with digital humanities projects. Unless a specific set of programs with great longevity and security are made part of the professional training for historians, these programs will remain the niche abilities of just a few of us.

My Future with Digital Humanities

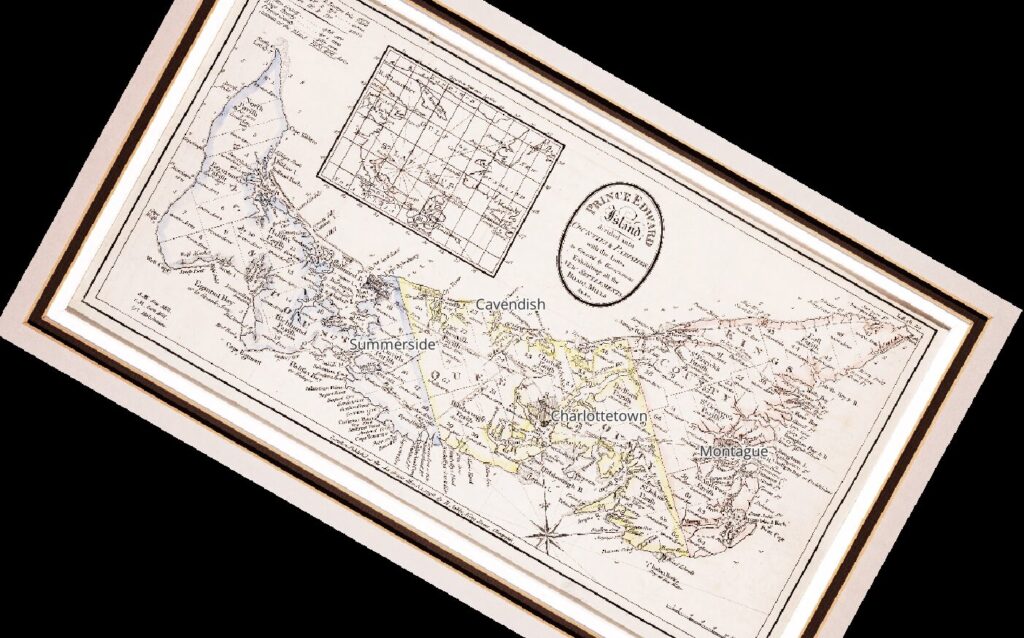

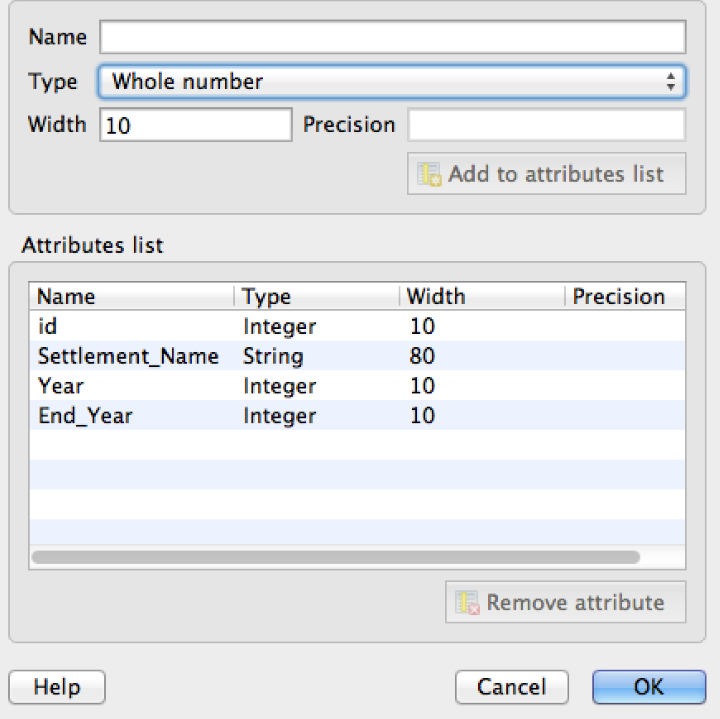

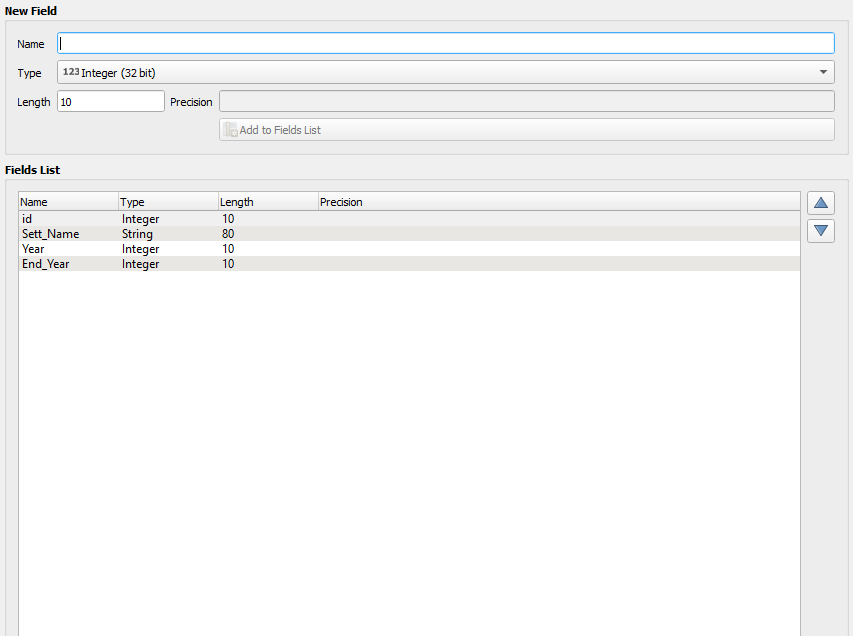

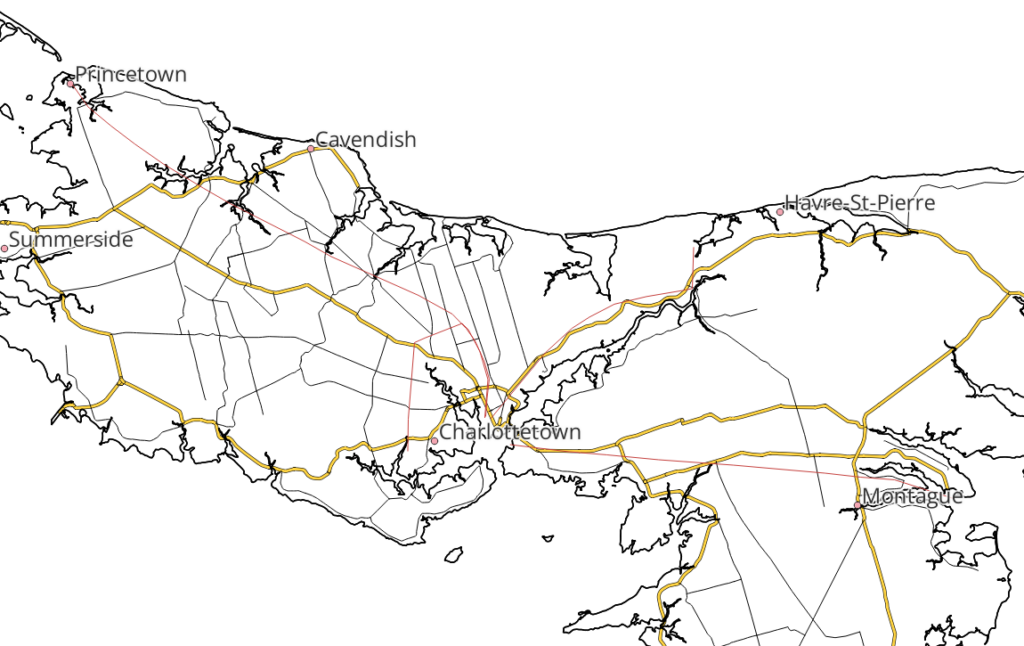

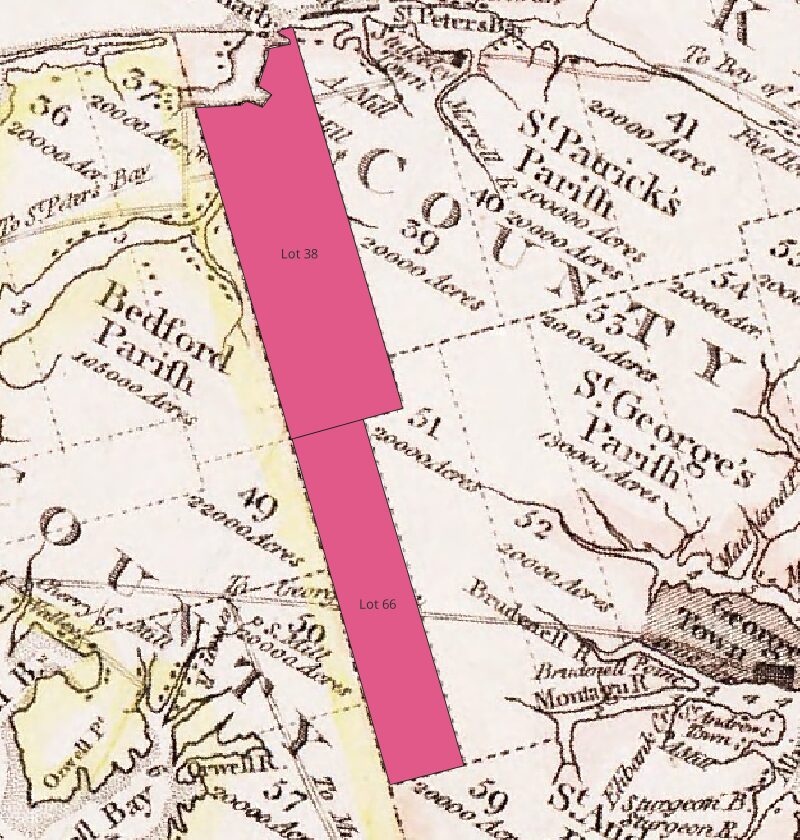

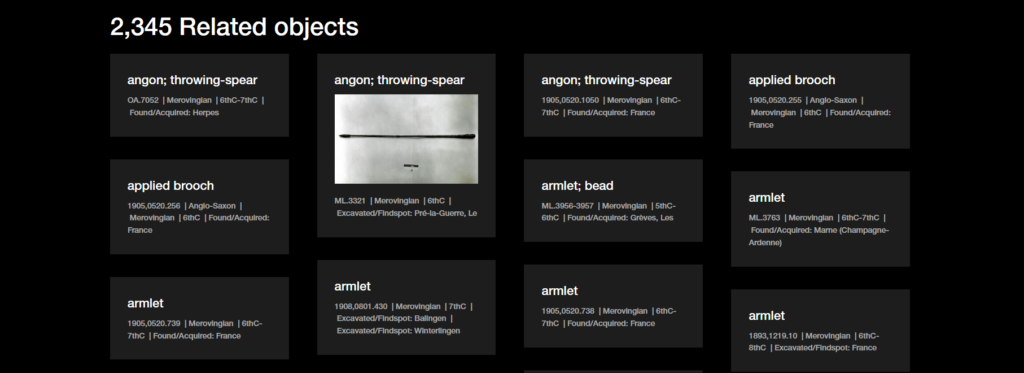

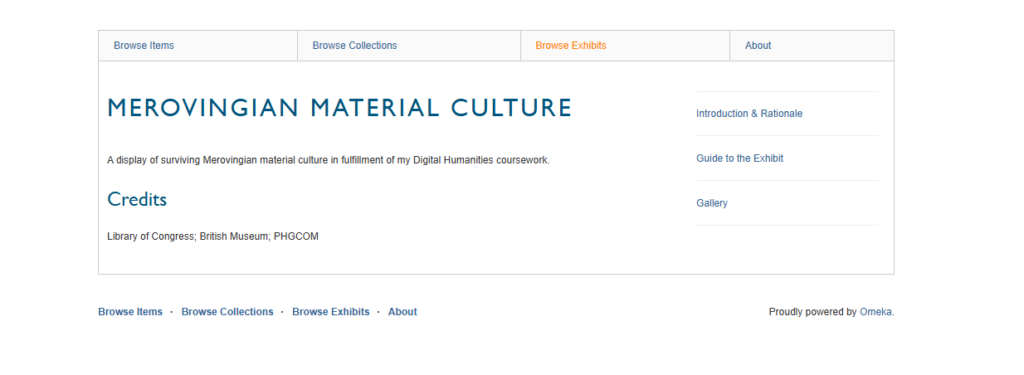

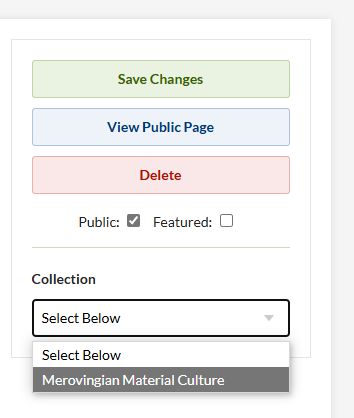

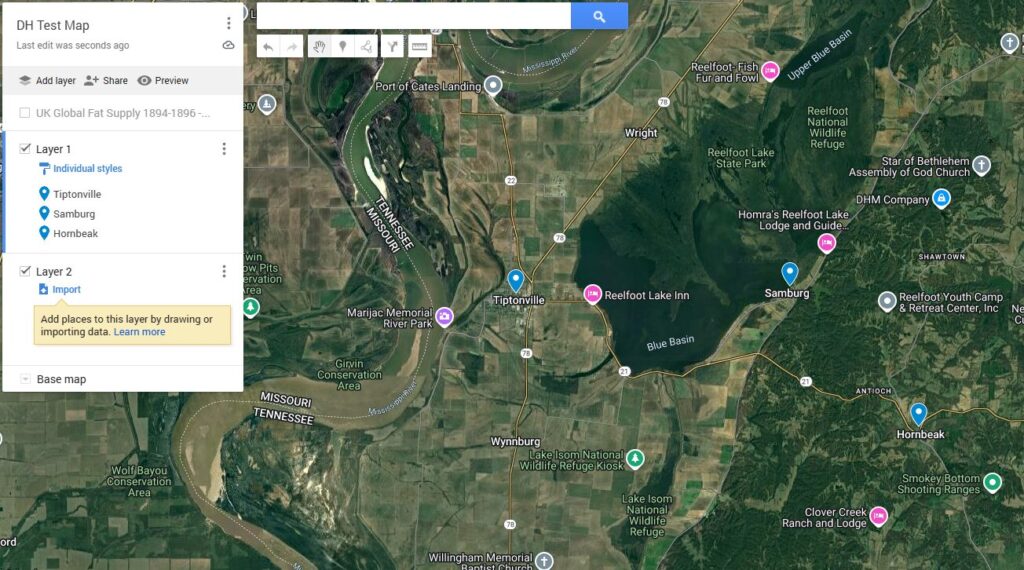

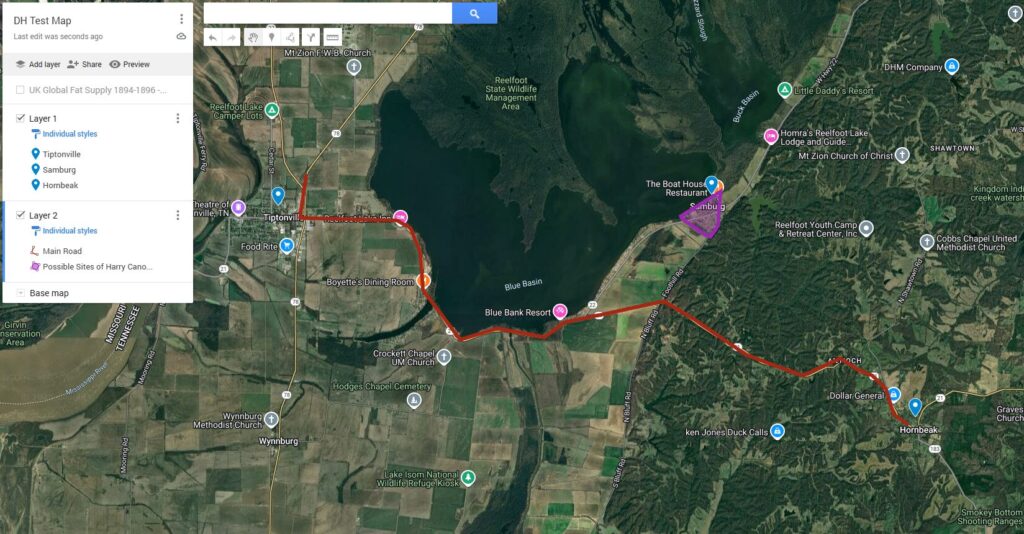

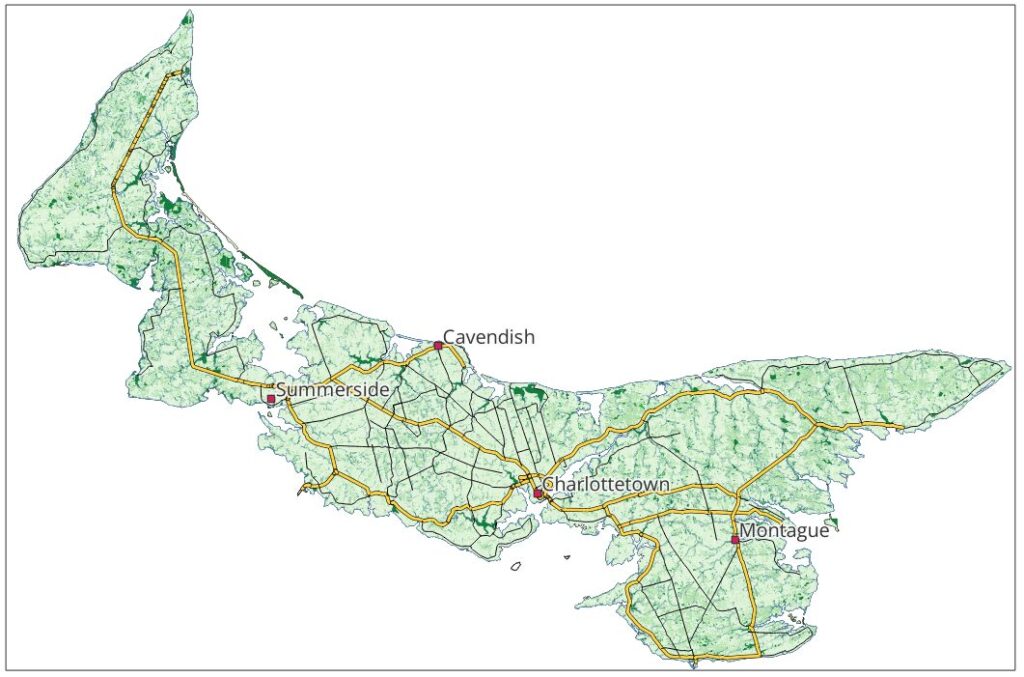

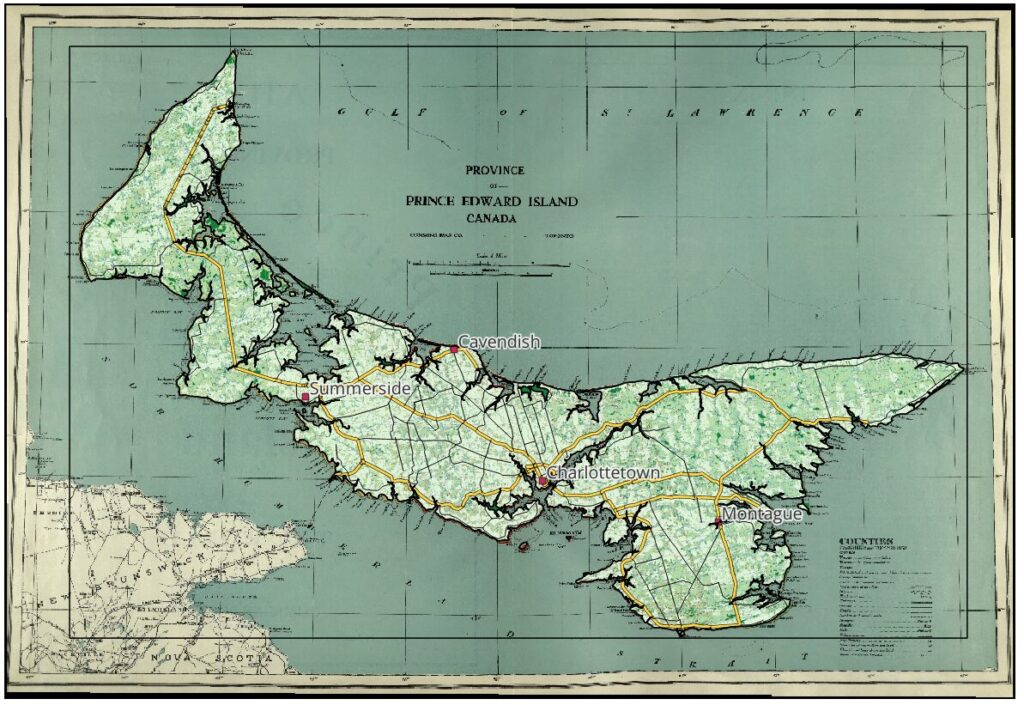

I plan to continue the use of both this website and the QGIS program as I move forward in my academic career. In particular, I hope to use QGIS to create an interactive map of Europe which will display text entries from Merovingian primary sources by their years and the locations referenced. This is something I originally did (in a limited format) on paper several years ago; the opportunity to expand it to a functional interactive map will be incredibly rewarding. At the same time, I’ll need a bit more training to make it happen. While I’m fairly certain I could make a decent mockup of what I’m looking for just using the layers window, I also suspect that QGIS has more specific tools buried in it that will help me with just what I’m looking for. In either case, I look forward to getting this project off the ground in the near future.